Area’s population has had a hand in philanthropy, the foundation of unions, workers and women’s rights and female suffrage

Subscribe to our free Wharf Whispers newsletter here

The world can seem an increasingly bleak place.

The relentless digital news machines deliver a steady diet of shock and awe at callous acts of brutality by humans the world over.

One antidote to this pipeline of 24-hour misery is to take a step back from the present to look back and realise how far we’ve come in some areas.

Roughly six and a half generations ago (191 years, to be exact), it was legal in Britain for one person to own another. It took a further 31 years for the USA to abolish slavery.

The freedoms and rights we enjoy today all have their roots in the toil and struggle of people who led lives unimaginably impoverished compared with our own and – in the grand scheme of things – not all that long ago.

This is precisely why we need to study history and develop places that showcase and highlight the collective achievements and missteps of our species.

a Heritage Pavilion on the River Lea

That is one of the missions that Cody Dock, an ecological regeneration project on the edge of Canning Town, is undertaking through its Heritage Pavilion project.

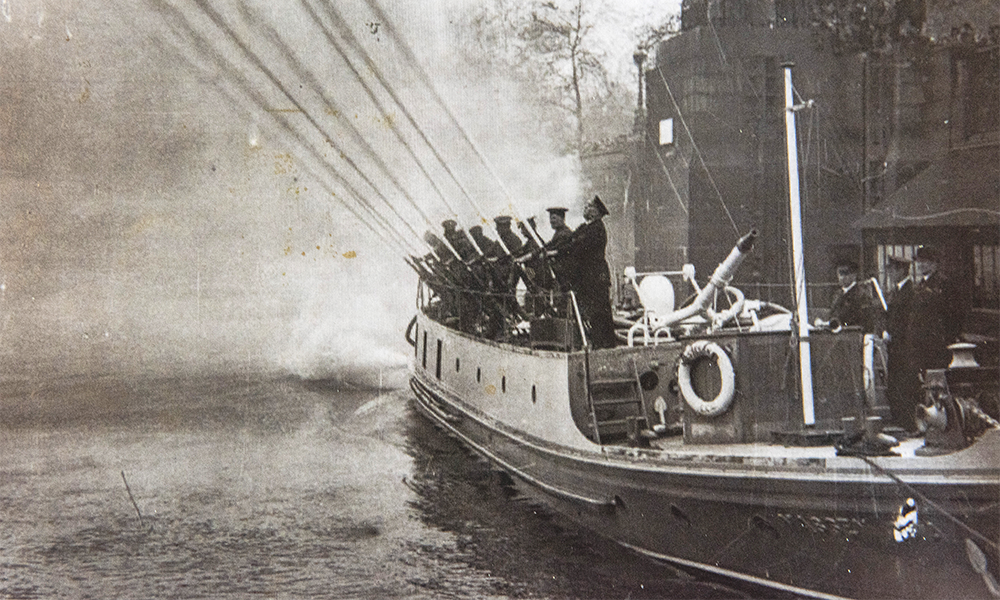

The structure will be built as part of a £1.6million National Lottery Heritage Fund grant, using the restored hull of Welsh lifeboat the Frederick Kitchen – likely the last vessel built at the Thames Ironworks – as its roof.

The glazed space will host quarterly exhibitions on the history of the area, with a special focus on the River Lea.

As anticipation builds for the pavilion’s launch, this is the second in a series of articles in a partnership between Wharf Life and Cody Dock to draw attention to some of the topics that will be featured.

The banks and marshlands around rivers are well known for their fertility.

The nutrient-heavy silts washed up by the constant flow of water, make for rich soils and abundant growth.

Factor in their historic use as corridors of trade, transport and migration and it’s little wonder that city waterways conveyed similar prosperity on the operations along their banks.

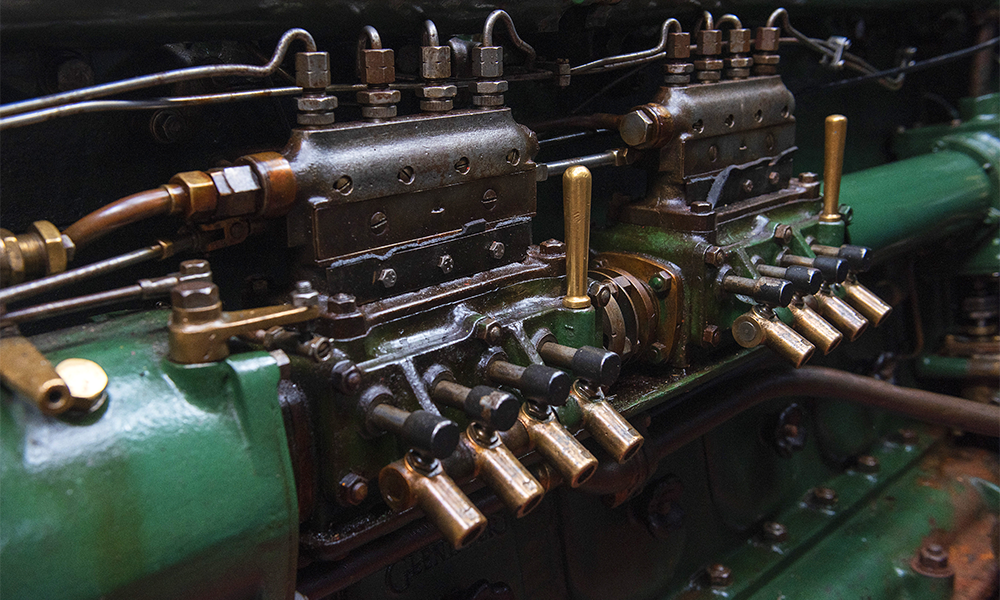

The Lea once bristled with industries that demanded sprawling communities of workers.

This human tide, forced to contend with extraordinary deprivation and shocking conditions, was in itself a potent force and one of the reasons east London has played an outsize role in the nation’s social history.

Here, people stood up, fought for better lives and succeeded. The four stories below aim to offer a flavour of just some of their remarkable achievements.

echoes of the past along the River Lea

Close to West Ham station, Berkeley Group is currently building a housing development called TwelveTrees Park.

That branding isn’t a reference to some long forgotten copse with a dozen pines, but a name from history.

The scheme is located on land near Twelvetrees Crescent, a road named for entrepreneur, factory owner, chemist, writer, campaigner and inspiring philanthropist, Harper Twelvetrees.

In his time, much of east London was a patchwork of industrial operations and slums, the latter housing the workers for the former.

The author Charles Dickens visited nearby Canning Town and wrote in 1857: “The houses are built in rows; but there being no roads, the ways are so unformed that the parish will not take charge of them.

“We come to a row of houses built with their backs to a stagnant ditch.

“We turn aside to see the ditch and find that it is a cesspool, so charged with corruption, that not a trace of vegetable matter grows upon its surface, bubbling and seething with the constant rise of the foul products of decomposition, that the pool pours into the air.

“The filth of each house passes through a short pipe straight into this ditch and stays there.”

Later on the same visit, he finds “three ghostly little children lying on the ground, hung with their faces over another pestilential ditch, breathing the poison of the bubbles as it rose and fishing about with their hands in the filth for something, perhaps for something nice to eat”.

Dickens’ bitterly ironic depiction of the dirty, blighted lives of the workers and their families around Bidder Street near the Lea is a stark picture of the kinds of conditions people endured a little over a century and a half ago in the name of industrial progress.

While plenty of business owners were content to exploit their employees, others had more progressive, compassionate ideas.

Born in Bedfordshire and originally apprenticed as a printer and a bookseller, Harper Twelvetrees developed an interest in chemistry.

Moving to London in 1848 he initially sold laundry products from other manufacturers in Holborn while working on a plan to make his own.

Having set up a small factory in Islington, in 1858 he moved production to a larger site on the banks of the River Lea at Bromley-By-Bow, just over the water from Three Mills.

Moving to the heart of the complex himself, he set about improving the lives of his workers – 400 at the peek of his Imperial Chemical Works’ success.

He built rows of cottages to house them, invested in a library, opened a lecture theatre, put on evening classes, organised sewing circles, created a clothing club and hosted non-denominational services.

There was even support for sick workers through a benevolent fund.

In 1861, the Stratford Times wrote: “Instead of dirty, narrow lanes bounded by high walls, now there are to be seen neat, commodious and well-built cottages, flanking tidy roads.

“The old population is losing its distinctive traits before a new, fresh and vigorous class that is rapidly settling amongst them and giving an air of busy life and incessant occupation to a place, which once wore an empty gloom hardly redeemed by the wild rush of waters roaring in the adjacent mill-stream.”

Philanthropy can be fragile, however.

Twelvetrees’ deal to sell his business in 1865 went bad, resulting in bankruptcy, although he did start up again on the other side of Bow at Cordova Works off Grove Road, eventually going on to produce washing machines and mangles.

lighting a fire

Collective effort is where lasting gains are often made.

While some workers in east London were relatively well treated by those making money off their sweat, others were not.

In July 1888, the women and teenage girls working at the Bryant & May match factory in Bow went out on strike.

There had been previous periods of industrial action over pay and punitive fines – sanctioning the often barefoot workers for dirty feet, untidy workbenches, lateness and dropped matches – but they had all failed.

1888, however, was different.

Atrocious working conditions including 14-hour days and the horrific ravages of phossy jaw – an industrial disease caused by exposure to the white phosphorus used in match production which killed a fifth of sufferers – were taking a terrible toll.

Social activists Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows became involved in the cause, publishing an article that angered managers at the factory, who attempted to get their workers to sign a statement repudiating its claims.

When they refused, a worker was fired – it was the spark that ignited the strike, with 1,400 women and girls walking out – probably on July 2.

Four days later, the whole factory had ceased to function.

The women had gone to visit Besant to enlist her help and with her support and the backing of some MPs, the strike generated significant publicity.

Besant – a prominent campaigner of a wide range of social and political issues – assisted in the negotiations and the workers were successful in getting unfair fines and deductions for materials abolished as well as a new grievance procedure with direct access to management.

A separate room for meals was also provided to prevent contamination of their food with poisonous phosphorus.

In the aftermath of the strike, the workers founded the Union Of Women Matchmakers – the largest such organisation of women and girls in the country at the time.

Their efforts inspired a wave of organising among industrial workers, the mothers of change.

fighting for workers’ rights

Canning Town Library played a significant role in that process.

In 1889 it was the venue for the formation of the National Union of Gas Workers and General Labourers.

Will Thorne, Ben Tillett and William Byford founded the organisation in response to lay-offs at Beckton Gasworks, with the former elected as its general secretary.

The organisation rapidly launched a successful campaign for an eight-hour working day, with its membership then rising to more than 20,000.

It was the start of a labour movement that eventually became the GMB union, which today has more than half a million members.

Also in 1889, the London Dock Strike saw a walkout by some 100,000 workers.

They won their pay claim for the introduction of the Dockers’ Tanner – a guaranteed rate of sixpence an hour – precipitating extensive unionisation across the sector.

It was against this backdrop that Labour Party founder Keir Hardie was invited to successfully stand for election as MP for West Ham South.

He represented the seat from 1892-1895.

women and equality

East London continued to play a crucial role in the development of workers and women’s rights.

From 1914 until 1924, 400 Old Ford Road in Bow was the headquarters of the East London Federation Of Suffragettes (ELFS), an organisation committed to getting women the vote and one based not far from where the match girls stuck their blow.

It was also the home of Sylvia Pankhurst and her fellow campaigner Norah Smyth as well as the location of their Women’s Hall – a radical social centre run largely by and for local working class women.

This included a larger space with a capacity of up to 350 and a smaller hall for about 50 – all furnished with tables and benches made with wood from supporter George Lansbury’s timber yard.

When the First World War led to unemployment and rising food prices, the hall opened a restaurant serving hot meals at cost-price with free milk for children.

Having broken with her mother – Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social And Political Union – Sylvia and the ELFS used east London as a base.

The group held marches through the neighbourhood, organised large public meetings, benefit concerts and parties as well as producing a weekly newspaper called The Women’s Dreadnought.

Other activities included opening a cooperative toy factory that paid a living wage to its female workers and even offered a crèche.

While the ELFS’s name changed over the years it remained active until 1924.

Today, the Suffragettes’ activities are remembered in a mural on the side of the neighbouring Lord Morpeth pub.

It’s stories like these that Cody Dock’s Heritage Pavilion will help showcase in greater depth when it opens next year.

Additional research by Cody Dock’s Julia Briscoe

key details: Frost Fair at Cody Dock

Cody Dock offers a wide range of volunteering opportunities and runs regular events and activities aimed at engaging with the local community.

You can find out more at its Frost Fair event on Saturday, November 29, 2025, which is free to attend from noon-5pm.

Read more: Why a degree in hospitality and tourism can boost your career