Museum Of London Docklands’ immersive exhibition takes visitors into boutiques and ateliers

Subscribe to our free Wharf Whispers newsletter here

“It’s been 20 years since the Museum Of London had a major fashion exhibition and this is the first time we’ve hosted one at Docklands – it’s also the first time we’ve done a major exhibition with London’s Jewish population at its centre,” said Dr Lucie Whitmore.

“The Museum Of London Docklands is the perfect place to share this story, because it’s about migration and creativity blossoming at the heart of east London.”

Lucie is curator of Fashion City at the West India Quay institution, a special exhibition that explores the impact of Jewish Londoners on global style, that will be in place for visitors to enjoy until April 14, 2024.

“It’s a celebration and recognition of the contribution that these individuals have made to the industry.

“We’re thinking about this in a very broad sense.

“We wanted to go beyond the stereotypes or what we think people might expect about the relationship between Jewish people and making clothes in London.

“We aim to encourage people to really think about how diverse our garment industry is and how many people are responsible for making the capital a fashion centre with an international reputation.

“To do this we’re taking our visitors on a bit of a journey.

“The exhibition is not structured chronologically, as people might expect, but geographically.

“So we have an East End and a West End and the places and spaces of London inform our structural approach.

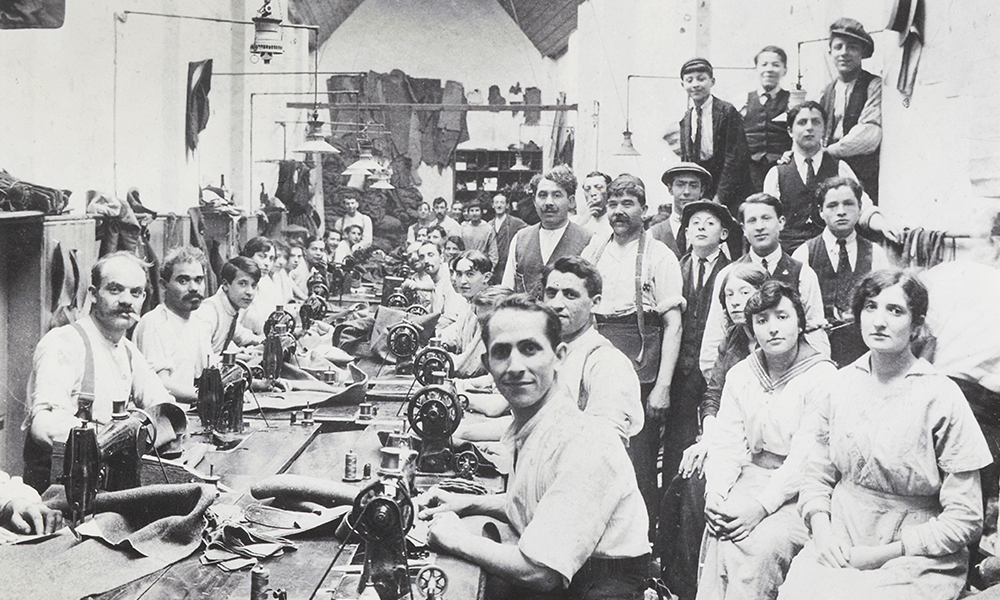

“There are a lot of misconceptions and stereotypes – and sometimes anti-Semitic thinking – about Jewish people in the east of London, what is known as ‘sweated labour’, for example.

“That’s the idea of Jewish people either being poor and persecuted without agency, working in horrible conditions, producing cheap clothes in the East End.

“At the opposite end of that scale, there are misconceptions about wealthy Jewish people profiting from the work of others.

“We really wanted to dig into Jewish life and work in the East End, and show that it wasn’t like this.

“Obviously there were people who were treated very badly in the trade, but there were also people who had amazing agency and set up their own businesses, not just in tailoring, but also in accessories, leather-work, dressmaking – there’s a lot more to the story.

“We also wanted to show just how important Jewish makers and retailers have been in the West End, which has a glitzier reputation.

“People think about grand department stores, high street chains, couture, the pinnacle of London fashion – and Jewish makers are really important in that story as well.

“Although we don’t go into it in great depth, I was really keen for people to know that there was a big and really important resident Jewish population in the West End.

“People had settled there for quite a long time, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th century.

“Soho and Fitzrovia were predominantly Jewish areas, and a lot of people don’t necessarily know that.

“The other reason for structuring Fashion City this way was that it allows us to examine different pockets of the industry by place, bringing together designers who knew each other and worked together or, perhaps, who were around at different times but did similar things.

“Visitors will be able to walk into an East End tailor’s workshop, step into the luxury of a couture salon and have a bit of a dance in our Carnaby boutique.”

While fashion is the core of the exhibition, there’s a thread of music running through things too.

The playlist includes the likes of the Mamas And Papas, The Beatles, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones and The Yardbirds who all wore clothes by designers featured in the exhibition.

“There’s Adam Faith too, who was a great customer of menswear shop Cecil Gee and we’re really excited to be featuring them all in Fashion City,” said Lucie.

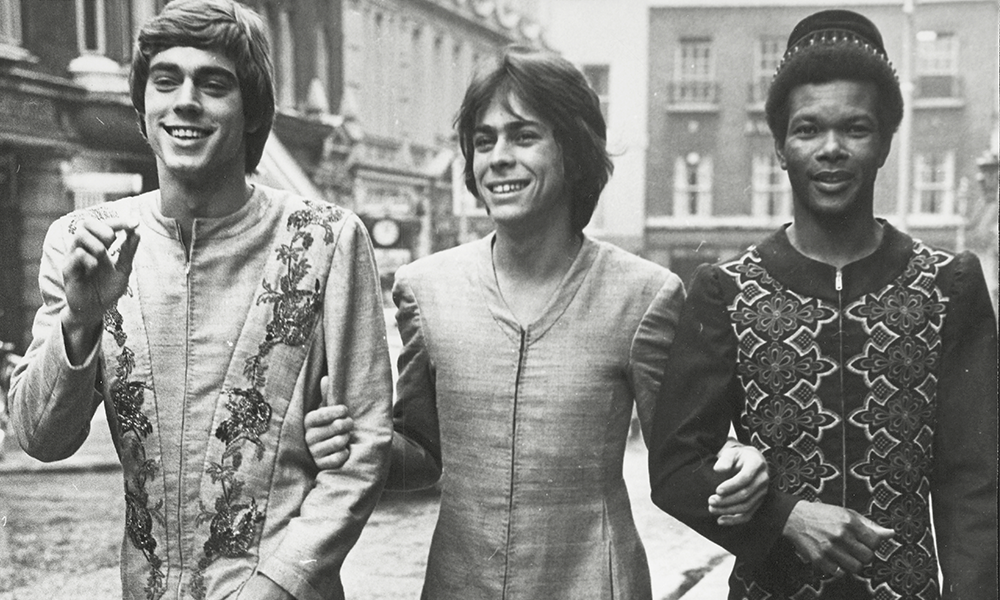

“It was also irresistible to include designer Mr Fish, who was in the spotlight in such a huge way in the 1960s.

“He was extraordinarily creative, known for his flamboyant menswear.

“He starts in Colette’s department store in Shaftesbury Avenue, moves around various retail jobs and eventually becomes established as a shirt maker.

“Then we get this classically trained designer who has developed all his skills and plays with the designs – subverts them, and then puts his creations in front of a different audience.

“He also invents the kipper tie.

“He gains the attention of several high-profile customers, such as Sean Connery and Barry Sainsbury, of the Sainsbury family, who goes into business with him.

“They open a boutique on Clifford Street between Jermyn Street – the traditional home of shirt making – and Carnaby Street.

“It’s the peacock revolution, with young, stylish customers – musicians, sports stars and actors – it’s also a place to hang out.

“There’s a story that an Italian film crew came to London to film in Mr Fish’s boutique, because they saw it as the downfall of British society and they wanted to capture the end of it.

“They saw Mr Fish as a beacon of change.

“He was doing skirts and dresses for men and felt that the male body was better suited to them – he called the garments powerful and virile.

“He wasn’t the first to do that, but the spirit behind his clothes was fascinating and heartfelt.

“Some people want to dismiss him as a bit of a novelty, but actually the quality of the design and the creativity, and how much he believed in it shows it wasn’t frivolity – it was fashion.

“The skirts and dresses were very popular and worn, very famously, by David Bowie and Mick Jagger. We also have a wonderful picture of an Arsenal footballer wearing one.”

The exhibition is filled with glamour. There are evening dresses, high-end hats and exquisite couture pieces.

The exhibition includes a coat by David Sassoon of Bellville Sassoon worn by Princess Diana and another by EastEnders royalty Dot Cotton in tweed by Alexon.

But Lucie and her team were keen to showcase the stories of real Londoners alongside the glamour.

The exhibition opens with the story of the 200,000 Jewish migrants arriving in the capital between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries through personal artefacts.

More than 50% would come to be involved in the fashion, clothing and textile trade.

Items include a small travelling case used by a child who came to London on the Kindertransport – the rescue effort to send children out of Nazi-controlled territory from 1938-39.

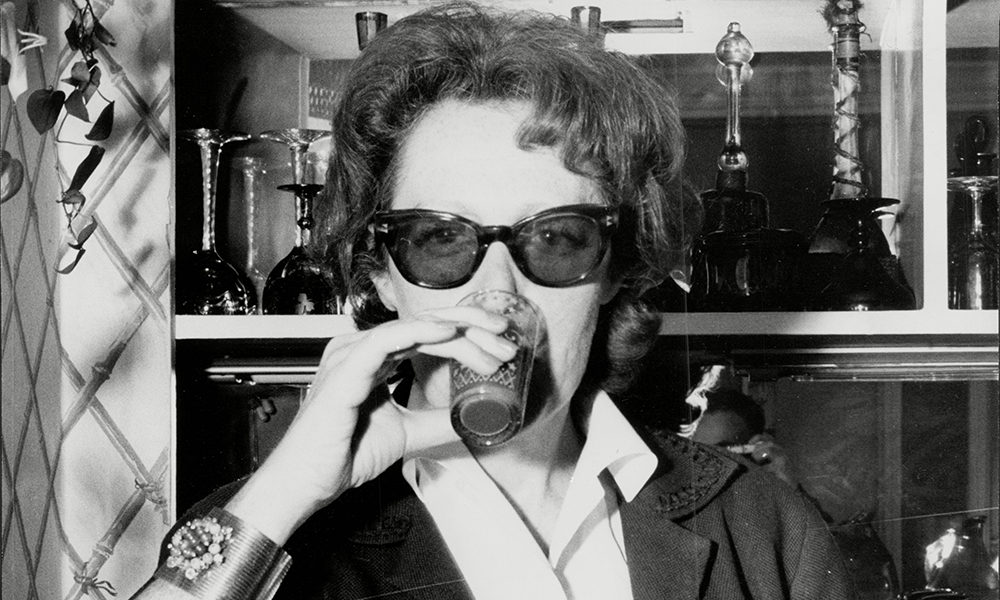

More than four years of research has gone into Fashion City and Lucie said one of the reasons she and collaborator Dr Bethan Bide of the University Of Leeds has wanted to explore the topic was the high level of resonance.

“We’d both done quite a lot of talking about it publicly and there was a lot of personal interest in the subject matter,” said Lucie, who began her career as a designer and became increasingly interested in the history of fashion.

“People who came to our talks recognised their own family stories and would feel quite emotional and proud of them.”

That’s partly true of Lucie herself, whose own family feature in the exhibition.

“They were Jewish refugees from Vienna,” she said.

“I should make it clear this isn’t a biased move on the part of the curator.

“We really wanted a story about leather goods and bags, and we didn’t have those objects already in our collection, but the story of my family fits perfectly in the narrative of the exhibition.

“The material was reviewed anonymously by an external reviewer for suitability before I put my great-grandfather in there.

“The family had already made one big move from Ukraine to Austria where they westernised their names.

“In Vienna they set up leather goods business Molmax, which was initially a big producer of sportswear, Alpine skiwear and leather goods.

“Then they moved into luggage, and they won a really big reputation internationally.

“But in 1938, after the German invasion, my family survived at great risk.

“Because my great-grandfather was a businessman, people would phone them and warn them when there was going to be a raid on their buildings, so they needed to be away.

“There’s an extraordinary story, which we do touch on in the exhibition, where some Nazi officers knocked on the front door of their home and demanded to be taken to the factory immediately.

“They took my great-grandfather and great uncle there in a van and took pretty much all their stock with no payment, nothing.

“Then they took over and Aryanised the factory.

“My grandmother and her brother left on the Kindertransport and my great grandfather managed to obtain a business visa which was how he managed to escape.

“My great grandmother was left to pack up the family home and make her own way over, and they were very lucky that they all reached Britain safely.

“There they re-established the business in London, starting off in Holborn.

“My great uncle, who was only 16, was the only one who spoke English and so he was doing all the work of translating and finding producers and places to work.

“They got it going and moved to Quaker Street, just off Brick Lane.

“They managed to grow another international business, with offices in New York, exporting all over the world, before it closed in the early 1980s.”

There is, of course, more.

There’s the Rahvis sisters who designed clothes worn by the likes of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell.

The flamboyant hats of Otto Lucas and an exploration of the connections between the Jewish community and other immigrant populations from the Caribbean and Bangladesh – seamstress Anwara Begum’s sewing machine is on display, which she used to make garments for local businesses at her home in Quaker Street.

In fact, there’s far too much on show to truly do the exhibition justice here – you’ll just have to go and see it for yourself.

Then for even more depth, you can dip into Lucie’s book, written with Bethan, to accompany the exhibition.

Standard entry to Fashion City costs £12 for adults and £6 for children.

Find out more about the exhibition or book tickets here

Read more: Sign up for the Santa Stair Climb at One Canada Square

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to our free Wharf Whispers newsletter here

- Jon Massey is co-founder and editorial director of Wharf Life and writes about a wide range of subjects in Canary Wharf, Docklands and east London - contact via jon.massey@wharf-life.com