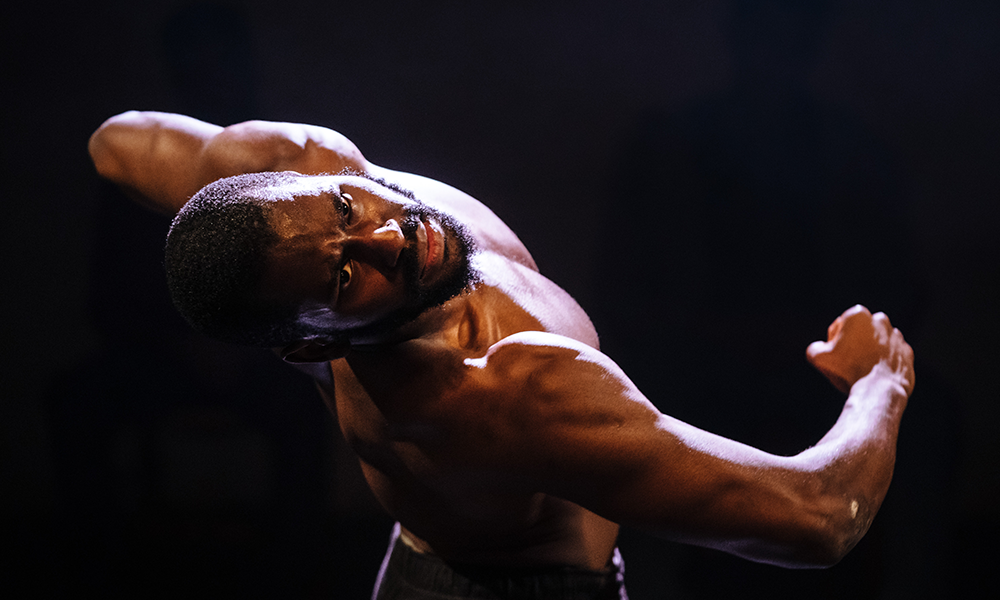

Lanre Malaolu’s work deals with the generational ties that can hold men back from emotional vulnerability

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

BY LAURA ENFIELD

I’m really starting to question what toxic masculinity means?” said Lanre Malaolu.

“I think ‘masculinity’ is just ‘masculinity’ and it can’t be toxic by its nature, just like ‘femininity’ can’t be toxic.

“Saying that is putting a taint on with a very broad stroke and going deeper is what I’m really interested in.”

The Hackney resident, writer, director and choreographer, accepts men aren’t as readily available to talk about their emotions, but he wants to know why.

“What is holding them back?” he said.

“What are the chains that we feel we need to hold? It’s a two-way street. Men feel that they need to be the breadwinner, protect and be the alpha to get along.

“Why and where that has come from is what I’m interested in, rather than putting something under the broad stroke of ‘toxic masculinity’.”

His thoughts spill out in his show Samskara – an exploration of black masculinity, vulnerability, and the cycles of fatherhood.

It returns to The Yard in Hackney Wick from June 27 until July 23, 2022, following a sell-out premiere in 2021.

It is a fusion of storytelling, movement, hip-hop, dance and text performed by five actors who play four generations of black men named Silent Man, Father, Wisdom, Young Buck and Older.

Lanre wrote, directed and choreographed it and said: “I find with shows, I may think they’ve come from one idea but really it’s an amalgamation of different events, moments and emotions that I’ve experienced over and over again in my life and that I’m finally ready to talk about and channel into work.

“My father wasn’t consistently present growing up and we had a quite fractured relationship.

“So I decided to sit down and really let him know how I felt.

“My voice was raised, my emotions were high because it’s been a crazy journey I’ve gone through growing up as a young boy into a man.

“I remember him listening, taking it in and then right at the end he apologised and said: ‘All I know is how my father was with me,’ and he started to speak about his upbringing. It was the first time I saw my dad as a son.”

Lanre began thinking about the generational cycles of fatherhood and what he wanted to pass on as a son and potential father.

He also began unpacking his interactions with other black men.

“There’s been conversations I’ve had with black men about black masculinity,” he said.

“There have been moments of no conversation, of walking down the street and nodding my head with another black man, something that is not really spoken about, but is so universally understood within the black male culture.

“I started to think about what is behind that? There’s love, joy, a bit of fear and, at times, solidarity. I thought: ‘What if we explore all those things?’.

“I did a workshop in HMP Thameside prison some years ago where I was really faced with the stark truth of what it is to be vulnerable as a black man.

“The idea was to explore sensitivity and touch. Getting the men to do that in an environment that didn’t promote vulnerability in any way was a real challenge, but it also birthed moments of real honesty.”

Lanre believes there is an untapped pool of willingness to talk about emotions but men are held back.

He said: “Because of walking down the street and, at times, being seen as a threat, because of needing to be perceived as someone that is strong and has their shit together, we then put that armour up and people with armour are on battlefields and don’t talk about their emotions. So we condition ourselves not to.”

Working class Hackney in the 1990s was an environment full of men putting on a front. But Lanre found his way through.

“I wasn’t a street thug, but I knew those guys and I could have gone the other way,” he said.

“When you have low income, poverty and a government that doesn’t seem to care, then of course these things are going to happen.

“There were hard times, times of joy and you grow and learn and keep walking your way through. Faith was an important part of that.

“Not just religious, but faith that there’s always an ‘and’ never just a ‘but’. When I get pessimistic I always feel like there’s a way through.

“Hope is always there in these communities. It’s not just pain and struggle. You go into a Nigerian wedding, or a black party and the flow of joy, love and abundance is there.

“I want to make sure that I always talk about that. This show is going to have that because that’s what it means to be black and a black man. There’s so much joy.”

He was “bouncing off the walls” as a kid, but found his joy through performing after his mum took him to the renowned Anna Scher Theatre school and he began booking jobs with the BBC and Channel 4.

In between classes, he and his friends would put on dance battles and Lanre co-founded company Protocol with the sole aim of performing at Breakin Convention.

They got their wish and more, when founder of the international hip-hop theatre festival Jonzi D “saw a spark” in them.

“They nurtured and cultivated it and then allowed us to kind of find our own continuous path,” said Lanre. “I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing without that support.”

He went on to study at Drama Centre London, but left early to join the Royal Shakespeare Company and, as an actor, appeared at the Royal Court and in Channel 4’s Hollyoaks.

It was being chosen for The Old Vic 12 – a scheme to help developing artists ready to take the next step in their careers – which garnered him attention as an independent movement director and, five years ago, Protocol ended “with love” so he could focus on the opportunities coming his way.

“It turned out to be the best thing, because I needed that space to create my own strand as ‘Lanre Malaolu the artist’,” he said.

That has involved I Can’t Breathe, a response to the police killing of black man Eric Garner in 2014, Elephant In The Room in 2019, which explored mental and emotional health in black men, The Conversation, a 2019 short film on communicating racial experience to white partners, and The Circle, a 2020 documentary digging into the dynamics of brotherhood between black men.

Samskara is his first full-length show with a cast and he said it “started without me knowing”.

“I reached a point in my life where I was able to talk to my dad and then follow through with other black men in an honest way and just try and understand more,” he said.

“I didn’t interview him because I find that isn’t the best way to have valuable conversations with black men because that’s when the guards come up.

“No matter what anyone says, you will be able to get more of the truth over a meal in Nando’s when the energy is right.

“I was watching, listening, seeing and mentally noting things and writing them down.

“I would be at my barbers where I’ve gone for 15 years and had so many conversations that I’m sure, in some way, have fed into the show.

“When the Samskara started to come together, I got these sharp, bursts of images and wrote them down.

“Then I started to think specifically about generations. I knew one character was going to be really young and think he could take on the world.

“One was going to be a father, one an older man who’s been weathered down. I started writing monologues for them, workshopped it for two weeks and, from that, it continued to build.”

He grew up a 15-minute walk from The Yard and said he was proud of how it had transformed over the years.

“They’ve changed and learnt and they’re really supporting artists to do their best work by giving space, really listening and putting their money where their mouth is,” he said. “I really respect and love that about them.”

He hopes Samskara will open up conversations and allow black men in the audience to see themselves in ways they haven’t been allowed to before.

“I still have a lot of chains to break myself, but I am able to talk about my feelings and my emotions in a way that I wasn’t 10 years ago,” he said.

“Hopefully, I can say the same thing in another 10 years, because I’m a work in progress.

“Making the show has allowed me to really challenge myself whenever I have interactions with black men, because I know and understand the pain.

“I think it’s the fault of a lot of things. Eddie Marsden said something brilliant about how when young boys grow up, they think they can be superheroes.

“Some men let go of that and some take it on and that’s what feeds into this feeling that they are able to have an upper hand on the female sex. It goes back to the things we are taught. That’s what this show is really about.

“What do we learn that we don’t even realize and how do we unpack and untangle and break those chains to move on?

“How do we accept that things like vulnerability are ultimately the superhero strength for a man, a black man.”

- Those aged 26 or younger can get £5 tickets on the door to all performances that are not sold out

- There will be shows on July 15 and 22 for black men and ticketed banquets for the black community on July 1 and mixed audiences on July 7 to encourage conversation

Read more: How businesses are tackling sustainability at Reset Connect

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

- Laura Enfield is a regular contributor to Wharf Life, writing about a wide range of subjects across Docklands and east London