Based at Art Hub Studios, the artist draws inspiration from Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

BY LAURA ENFIELD

What do a Nobel Prize-winning Kenyan environmentalist and a Scottish-born sculptor based in Deptford have in common?

Both felt overwhelmed by the raging environmental issues facing the world and decided to take action, no matter how small.

In the 1970s Wangari Maathai spoke of a hummingbird trying to put out a forest fire with tiny drops of water while larger animals disparaged it for being too small to help. It replied: “I’m doing the best I can”.

“That for me is what we all should do,” Wangari said.

“Be like the hummingbird. I may be insignificant, but I certainly don’t want to be like the animals watching as the planet goes down the drain.”

She went on to help reforest swathes of Africa and founded the Green Belt movement.

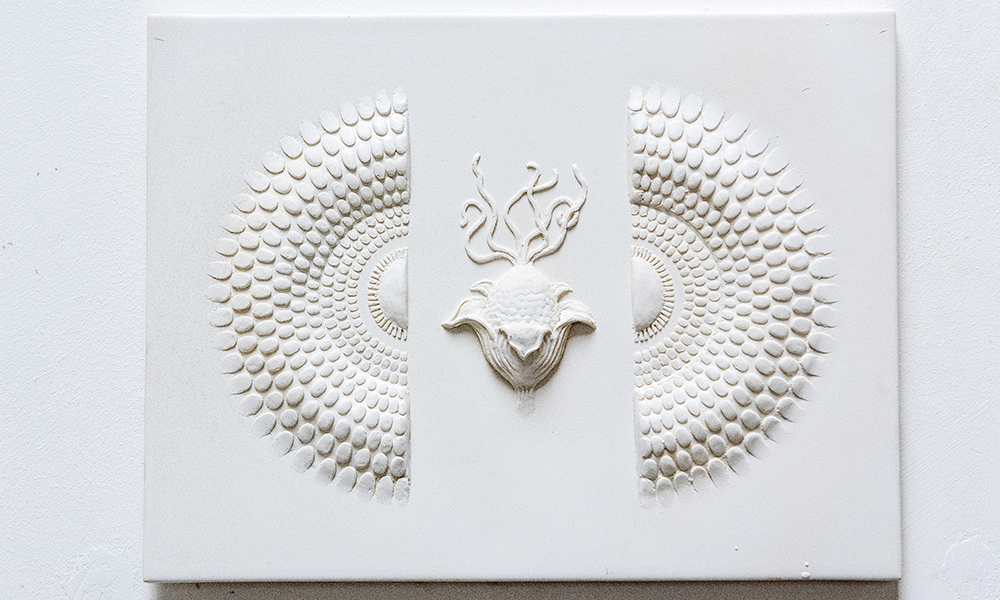

Half a century later, Deptford creative Dot Young is celebrating Wangari’s story with a series of delicate relief sculptures and is seeking to make her own practice as sustainable as possible.

“I work in an industry that is quite environmentally impactful,” said the 58-year-old, who has been based at Art Hub Studios in Creekside for the last decade.

“It’s on the consciousness of makers, about how what we’re doing impacts the planet. I don’t use resin anymore and I’ve been experimenting with more environmentally friendly materials.

“As a sculptor, you can get caught up in lots of non-biodegradable plastics that aren’t really appropriate anymore.

“I also run a degree course in prop-making at the Royal Central School Of Speech And Drama and I’ve been turning the focus to not ordering as much timber and using thick cardboards.”

Her work on Wangari is part of her Natural Formations series, which celebrates habitats, the environment and activists.

She has based much of it on 19th Century illustrative prints from environmentalists and botanists.

She has crafted the reliefs from hard plaster or jesmonite, a more sustainable alternative to resin, and has been experimenting by casting with different papers.

Dot said to find eco-friendly methods we only needed to look back.

“I worked in Venice for a short period with the mask makers,” she said.

“The traditional Venetian mask is actually made from a woollen paper called carta lana, soaked into a plaster mould and coated in sermel gesso, another environmentally friendly, ancient material.

“This method eventually got usurped by Chinese vacuum-formed plastics.

“It’s really interesting when you turn the clock back and look at what things were made of, pre-industrial revolution.

“You find ways of making that can be reinvented in a contemporary style.

“I’m interested in experimenting in mixing dust with gum arabic.

“The possibilities are endless for looking at how you might develop a new material.”

Dot first became more conscious of eco issues through her project Chair, which tracked the history of an oak chair from the forest where the tree had grown, to the sawmill and then the furniture manufacturer.

“The only chair I could find that was fully made in Britain was from High Wycombe,” she said.

“It made me realise we don’t have a furniture industry in the UK anymore, which is very sad.

“Then I moved on to tracking other things, like hair extensions I bought in Dulwich, which I traced back to Chennai in India.

“I was getting very aware of the globalisation of materials and doing the work to give people an idea that there was a responsibility around the objects we buy, of knowing where they come from, how they’re manufactured, if people have been exploited and their carbon footprint.

“It actually got quite intense and depressing. The reality was very overwhelming.

“I could have become a political activist but I decided to go back to the studio, because I wanted to find a way to celebrate nature.”

Dot began looking at the work of people who had archived natural phenomena, such as Ernst Haeckel.

To capture them in 3D she started using a method she calls slow sculpting, allowing whatever time is required to complete each piece.

She believes that having this intense and intimate relationship with the work is communicated in the outcomes.

“I’d been doing a lot of sculptural installation work until then,” said Dot.

“It had been very conceptual and I was craving the technical challenge of traditional sculpture.

“I did some completely out-there pieces, inspired by 19th century cakes but really wanted to get more intricate, and I’ve always felt relief sculpture was something a little bit tangential to the rest of the sculpture area.

“It’s all around London if you just look up and, historically, it’s a way of telling narratives used by the Egyptians, Romans and Greeks.

“I really enjoy the technical challenge and creating stories within the work.”

It is a stark contrast to her commercial work, which has included making heads of political leaders such as Barack Obama for Oxfam.

“That work can be really fun and I like working for organisations that are making a difference,” said Dot.

“But it is fast and furious and I have to produce it to a high standard.

“What I really love about the relief work is that I don’t put a time limit on it. It will take as long as it takes to get it right.

“When you spend that time laboriously doing it again and again, it’s very meditative but it also speaks of slowing down and spending quality time doing something that’s hopefully, valuable.”

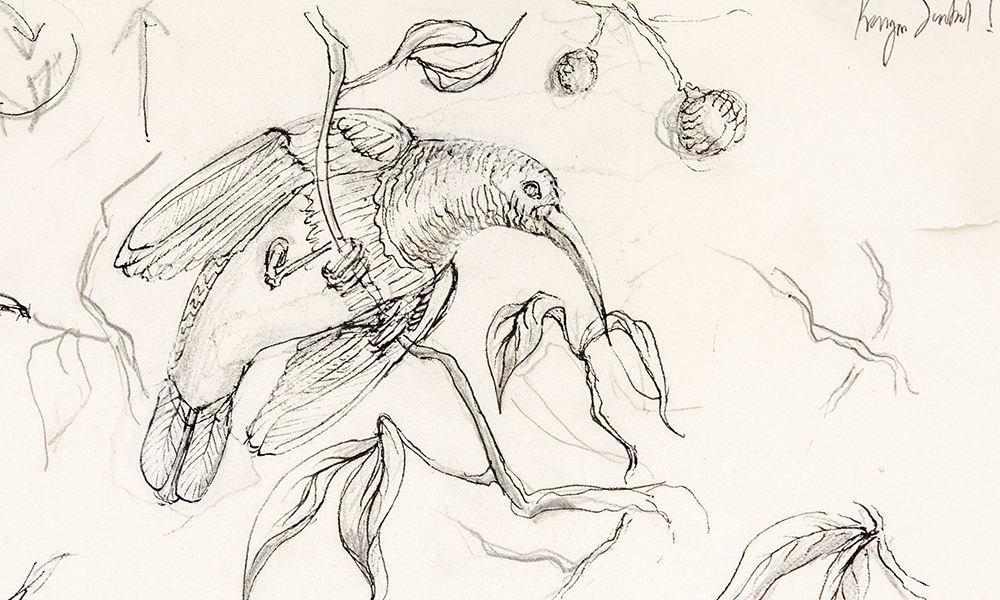

Each piece starts with lots of drawing and collaging to come up with a design, which is then transferred to a wooden board.

From there, Dot hand sculpts the design using polymer clay, which doesn’t dry out quickly – meaning she can spend several days or weeks on each piece.

Once the sculpting is finished, she makes a mould of the piece and casts it. She then sculpts out any imperfections and moulds and casts again.

“That makes it a very flexible process with lots more opportunities to add, take away and change it along the way and have a wider variety of outcomes,” said Dot.

“Sometimes it can be really frustrating. If it’s a really complex one, I do sometimes feel a bit overwhelmed if I can’t get it to work.

“But I know from experience that I just have to walk away, leave it and then come back to it.

“It’s definitely not a simple, linear process. Sometimes I do a drawing I think will work in relief, but then it doesn’t.”

“The work can’t just be decorative – I’m not really interested in that,” added Dot, who runs sculptural workshops and classes with Action For Refugees in Lewisham and has created experiential sculptural work for dementia-suffering residents in care homes.

“It’s got to have something that’s either powerful in its symbolism or be beautifully mathematical and geometric.

“I love Islamic art because it relates to the universe and secret geometry.

“That’s been a big influence.”

Born in Edinburgh, Dot was introduced to the joy of objects and making by her father, a mechanical engineer, who was at the forefront of developing lasers.

After studying sculpture in Sheffield, she moved to London and was swept up in the 1990s era of shared housing, cooperatives and artist squats.

She then spent time in Africa, sculpting across Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa and in the Tenganenge Sculpture village in Zimbabwe, which is another reason for her interest in Wangari Maathai.

Dot has already sculpted a panel inspired by the environmentalist featuring a croton seed, associated with the Kenyan reforestation programme and the African fabric associated with Wangari.

She is now working on a larger panel for the Craft In Focus event at Hever Castle in Kent (Sept 8-11, 2022), which will feature, hummingbirds, naturally.

“It will make a larger statement about her narrative – about how you can make a difference, no matter how small the effort you make,” said Dot.

“People that genuinely have an awareness of the environment are drawn to this work.

“There’s quite a limited audience when you’re doing really specialist installation pieces, whereas the work I do now is more commercial so I feel the audience is wider.

“Communicating with more people means I have a bigger voice, which I’m really enjoying.

“When people ask what it’s about then I really get to talk about the state of the planet and how my work is motivated by the concerns we have – but not in a negative way, kind of a celebratory way.”

Read more: How Unifi.id can help building owners cut carbon

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

- Laura Enfield is a regular contributor to Wharf Life, writing about a wide range of subjects across Docklands and east London