Historic ship’s move is the start of the latest chapter as Trinity Buoy Wharf prepares her for opening

Subscribe to our free Wharf Whispers newsletter here

So there she sits, resplendent in her red and black livery, atop a specially constructed pontoon and ready for the next chapter of her life.

The SS Robin has, after some 133 years, returned to within 150m of the shipyard where the iron plates of her hull were first riveted together.

She might be smaller in size than the Cutty Sark and HMS Belfast – but make no mistake – as historic ships in London go, she’s deserving of attention.

And following her most recent relocation from Royal Victoria Dock to Trinity Buoy Wharf, the story of the only surviving Victorian steam ship in existence is a big step closer to getting appropriate prominence.

It’s a move that’s been a long time coming.

Having spent a chunk of her retirement (1991-2008) at West India Quay opposite Canary Wharf, the Crossrail project saw her moved to Suffolk, with funding secured for restoration.

That saw her lifted from the water and mounted on a pontoon in 2010, with the intention of returning her to Docklands for public exhibition.

But plans to open her as a museum ship in Royal Victoria Dock faltered so, while she has been moored near Millennium Mills since 2011, she’s remained mostly closed to the public and inaccessible.

Schemes were mooted, plans made and locations suggested, but in more than a decade, Robin failed to find a permanent home.

A site was not forthcoming in either the Royals or West India Docks, amid the ironically choppy administrative waters of the bodies managing these vast human-made lakes.

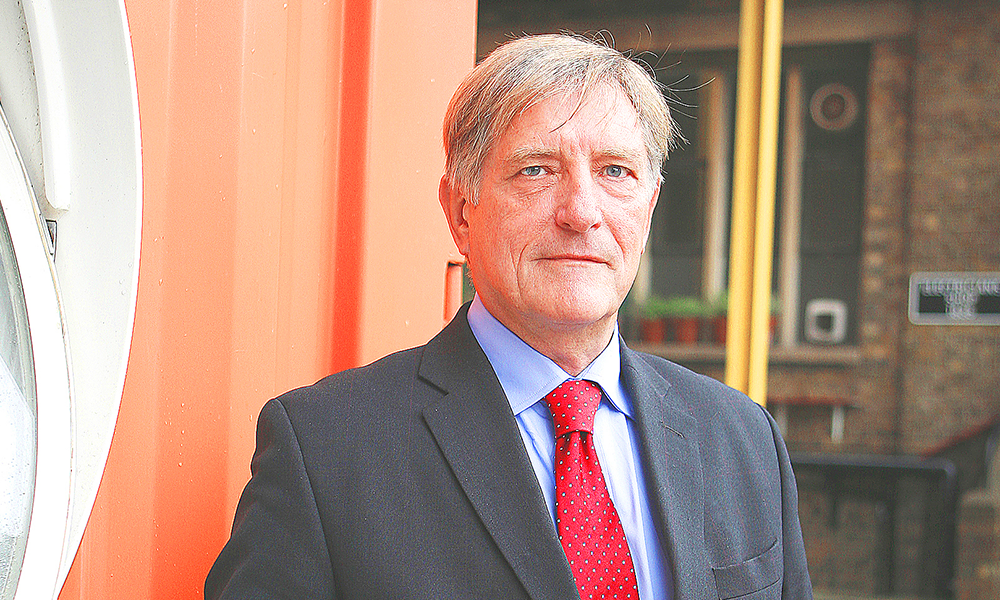

Eric Reynolds is founding director of Urban Space Management, which runs Trinity Buoy Wharf.

He is a man who makes things happen. London is strewn with projects he’s had a hand in – Camden Lock Market, Gabriel’s Wharf on the South Bank, Greenwich Market and Merton Abbey Mills, to name a few.

After becoming involved with the SS Robin and growing frustration at the failure to open her to the public as promised, he’s now overseen the relocation of the vessel to the mouth of the River Lea, where she will have a permanent home among the growing historic fleet at Trinity Buoy Wharf.

“The original intention was to keep going with the project and leave Robin where she was in Royal Docks,” said Eric.

“But eventually I gave up – I just couldn’t get any of the organisations to get off the fence.

“So instead we turned to the Port Of London Authority to get a licence to drive two piles into the riverbed at Trinity Buoy Wharf.

“The ship and her pontoon probably have a combined weight of about 600tonnes, which is not something I’d want to moor directly against the listed river wall as it would pose some risk.

“So, instead, it’s held between two giant ‘knitting needles’, which weigh 17 tonnes each. There’s a seven-metre rise and fall of the tide, so Robin will demonstrate that every day.”

That change in level also presents the last significant stumbling block to opening the vessel to the public.

A 40m gangway is set to be installed over the next couple of months that will go up and down with the level of the water, providing access at a suitable gradient.

Then, members of the public will be able to tour the vessel and view a wealth of information about her past and why she’s been preserved in this way.

“The driving idea is to make that information and Robin herself available to people who live here and know the area, as well as newcomers to it,” said Eric.

“There’s a population the size of Swindon scheduled to move in – a whole new town is being created.

“Shipping is still the major way by which the world trades with itself and London is here because it was driven by this tidal river and the trade that took place on it.

“Robin is the very last complete trading vessel of the period in the world with its original method of propulsion still in place.

“She was sold reasonably early in her life to the Spanish who operated her on a bit of a shoestring, so they didn’t do what nearly everyone else did, which was to take out the steam engine and put in an easily operated diesel.

“When you look at the ship and see the small size of the rudder and the huge propeller, you realise she’s relying on torque rather than revs.

“I really take my hat off to her crew – operating her in a crowded dock. With modern vessels you have bow thrusters and they can turn on a sixpence whatever the weather.

“With Robin you’d have had to spend 12 hours just getting steam up – their lives were so hard. We have a lot of material about her working life so we’ll be able to tell people all about it – the crew on her maiden voyage, for example.

“What we won’t do is commercialise her in any way – the whole point about this ship is she looks and feels like one that would carry coals from Newcastle and salted herring from Aberdeen.

“That should be respected and the entire idea is to create a free access open museum, along the lines of Blists Hill in Shropshire, where people can come to learn.”

Trinity Buoy Wharf plans to work with a cross section of organisations including schools, artists and musicians to explore and illuminate the vessel’s heritage as a jumping off point for study, not least in the fields of science and technology.

It also intends to tell the story of the ship’s construction at the yard of Mackenzie, MacAlpine And Company in Blackwall.

“That’s really quite amazing,” said Eric.

“With health and safety now, we could never imagine a 14-year-old boy throwing lumps of red hot metal up for someone else to catch in a shovel.

“The majority of the ship is original, and when we cut some of the metal and sent it away, the people said that you couldn’t get iron like this any more.

“It was probably made by some process that you wouldn’t be allowed to do now.

“For young people it’s a window into a lost world – an educational asset rather than a tourist attraction.”

In time, Trinity Buoy Wharf plans to bring all the historic vessels in its collection together with row barge Diana and the tugs Knocker White and Suncrest connected to the SS Robin, so visitors can tour all of them.

Watch this space for an opening date for the historic vessel.

Find out more about the SS Robin at Trinity Buoy Wharf here

Read more: How Canary Wharf’s Creative Virtual is taming the voice of AI

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to our free Wharf Whispers newsletter here

- Jon Massey is co-founder and editorial director of Wharf Life and writes about a wide range of subjects in Canary Wharf, Docklands and east London - contact via jon.massey@wharf-life.com