National Lottery Heritage Grant funding is crucial for plans to put in a lift and covert the crypt

Subscribe to our Wharf Whispers newsletter here

St Anne’s Limehouse has a long history of welcoming and protecting the people of east London.

Completed in 1727 to a design by Nicholas Hawksmoor, the towering white structure is home to a diverse congregation under current rector, the Rev Richard Bray.

But the church also has a long history as a place of refuge for all, with its crypt converted into a bomb shelter for local residents in the 1940s during the Second World War.

Today, that partly refurbished space offers a place for the homeless to sleep in safety.

However, the church and Care For St Anne’s (CfSA) – the charity whose mission is to conserve and celebrate the building’s architectural heritage – have ambitious plans to go much further.

In addition to restoration and refurbishment, they want to open the building up to a wider audience with a scheme that should see its doors flung wide beyond the timings of services and its regular Friday and Saturday opening hours.

To that end, CfSA recently received some £613,000 from the National Lottery Heritage Fund to launch its Hawksmoor 300: A Landmark For Limehouse campaign.

This is money it will use to move forward with an application for a further £2.9million National Lottery Delivery grant from 2025, as part of a £7million scheme to remodel significant chunks of unused space and improve access to the building by 2030.

“This project will infuse our historic building with fresh life for future generations, establishing it as the East End’s biggest, most accessible and welcoming community space,” said Rev Bray.

“We look forward to welcoming many of our neighbours into the renewed building before too long.”

There are really three parts to the project, as outlined to me by CfSA chair Philip Reddaway on a recent tour of the building – the steps, the crypt and the garden.

“There are a number of things we intend to do,” said Philip.

“First of all, there’s no step-free access to the church, which really doesn’t work in this day and age.

“Our plan is to install a lift from the crypt level to the nave and up to the gallery, which is a major project in itself. In terms of the building, the other big thing is the crypt.

“Part of it was cleared and refurbished in the 1980s with funding from the London Docklands Development Corporation.

“While that part is being used, it’s mainly for the church itself and we want to create a flexible, multi-use space – rather like Christ Church Spitalfields – that we can open to the wider community.

“That’s one of the things you have to demonstrate to get the Lottery funding – that it’s a project that will benefit and be used by a wide range of local people.

“At present, there are still more than 100 bodies buried in the crypt in walled off family tombs dating from the 18th century.

“You had to be rather grand to be interred here rather than in the churchyard, but as part of this project those spaces will need to be cleared and the remains reburied.

“That’s a complicated process and there are lots of specialists involved to ensure all the correct procedures are followed.”

The unconverted space is also littered with decades of detritus – the dumped ephemera of operation, placed out of sight and out of mind.

A further challenge for the renovators is the extensive network of blast walls and facilities left over from its time as a wartime bomb shelter.

These include ancient toilet cubicles and a pair of sick bays for Londoners to use while the explosives rained down outside.

“When we carried out our consultation, we found some people thought the church had been deconsecrated because the doors were often shut when no services were taking place,” said Philip.

“We now have a team of volunteers opening up on Fridays and Saturdays to help change that.

“But it’s not just being physically open, it’s about building on the things we already do – creating all sorts of partnerships with local organisations.

“We’re working with Queen Mary University, the Museum Of London Docklands, Whitechapel Gallery and the Building Crafts College in Stratford.

“Queen Mary’s history department, for example, spent time finding out more about the lives of the people buried in the crypt and gave a presentation about some of them.

“Sadly, but inevitably, this was one of the great shipbuilding areas of London, and several buried here were involved in the slave trade and we have at least one major slave trader buried here.

“We don’t walk away from that and I would like to see a permanent exhibition putting it in context.

“Another interesting finding was two brothers – John and Samuel Seaward – who lived near my home on Newell Street.

“They were maritime engineers who were involved in pioneering the first transatlantic steam ships – big cheeses in their field at the time.

“Queen Mary’s engineering department used their story as inspiration for a project with Cyril Jackson Primary School in Limehouse that saw 10-to-11-year-olds build boats in the spirit of the brothers, to help them learn basic engineering principles, with a view to building a working boat that can sail on one of the local canals.”

In addition to opening a cafe in the crypt, another of the ambitions for the Hawksmoor 300 project will be to update the church’s grounds.

“We want to create something called the Remembrance Garden to commemorate the waves of migrants who have come through Limehouse over the years,” said Philip.

“From the Huguenots, the Jews, the Chinese, all the way through to the Bangladeshi community, we want to have different parts of the churchyard planted to reflect the people who have settled here so there’s something that’s relevant to all of them.

“We’re working with a great charity called Groundwork, who are specialists in this kind of thing, as well as with pupils at Cyril Jackson to create this.

“The churchyard is lovely – dog-walkers love it – and it’s one of the biggest green spaces in the area, but it is under-utilised and we want people to come here and enjoy it.”

CfSA is now embarking on a fundraising campaign to raise a further £3.5million in addition to the £3.5million anticipated from the Lottery.

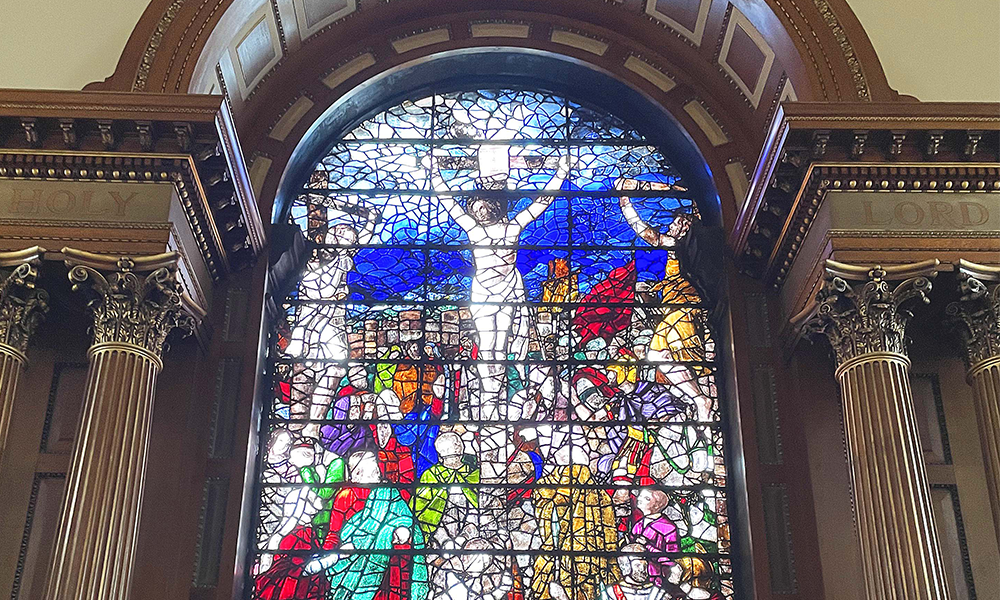

This latest drive comes off the back of another successful project, that will see the church’s massive stained glass window removed, restored and put back in place.

During the 12 months or so that it’s absent from the massive arch in the church’s east wall, a replacement window by artist Brian Clarke will occupy the space before it finds a new home, hopefully in the East End.

Then, following more than £100,000 worth of work, the original window will return to pride of place, its panels cleaned and the extensive buckling of the metal frames rectified.

“Inside, the church requires quite a lot of cosmetic attention, which has to happen to tackle the legacy of water getting in and things like that,” said Philip.

“But when the window returns, it will be another wonderful asset to the building opposite the fully restored organ that plays beautifully.”

Anyone interested in getting involved with the project in a fundraising or volunteering capacity can find out more online via the charity’s website here.

Read more: How WaterAid uses dragon boats to raise money

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to our Wharf Whispers newsletter here

- Jon Massey is co-founder and editorial director of Wharf Life and writes about a wide range of subjects in Canary Wharf, Docklands and east London - contact via jon.massey@wharf-life.com