Workshops will also be on offer for those who want to have a go at typing out their own pieces

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

When I was a young child, my parents gave me an old typewriter to play with. I loved hitting the keys, hearing that distinctive, hypnotic clacking sound, twisting the knob that made the roller revolve.

But I couldn’t really comprehend what it was for. Even though this was the 1980s, by the time I came of age to make marks on paper, computer keyboards had already replaced the old mechanical machines with their inky ribbons and staccato rhythms. Fun for a kid – a relic of a bygone age, perhaps – but nothing more.

It’s fortunate James Cook didn’t have that experience.

While studying A-Level art in 2014, he developed an interest in inventive ways to make marks, drawn to David Hockney’s iPad paintings.

“Then I came across Paul Smith, who had used typewriters,” said James. “What really caught my attention was his story.

“Born in 1921, he suffered with cerebral palsy his whole life. At the age of 11, his parents gave him a typewriter because he couldn’t hold a pencil.

“But, instead of writing, he ended up creating drawings, which was his passion. He only learnt to speak and walk as an adult, but at the age of 11 he was already creating these amazing pictures – drawings of the Mona Lisa and it fascinated me that it was even possible to do such a thing.

“Immediately after I had read about him, I started trawling around charity shops trying to find a typewriter – at first without much success.

“Then an elderly couple in one of the shops overheard that I was looking for a typewriter and told me that they had one belonging to the man’s late mother.

“It had been sitting in the attic for about 40 years, not being used, and they suggested that I could come round and collect it.”

After a few squirts of WD40, James got the mid 1950s Oliver Courier going and began to experiment.

“I was lucky I picked that typewriter up and that I didn’t give up straight away,” he said. “As time has gone on, I’ve discovered that there are some models that just don’t work for this kind of work.

“But what I had was a very expensive, very mechanically precise machine. If this hadn’t been the case I might not have stuck with it.”

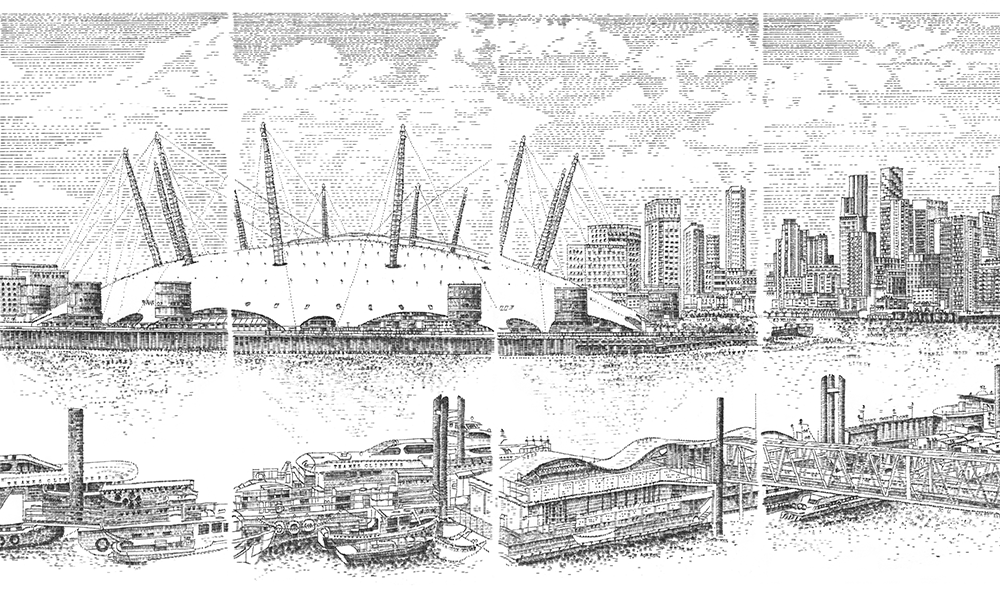

Perseverance paid off however and James now makes his living generating work on his collection of 40 typewriters, painstakingly using them to tap out artwork, either from life or photographs.

It’s exacting work, with drawings typically taking between a week and a month to complete.

“Usually the typewriters have 44 keys, so I have those parameters to work within and choosing the characters to use is one of the most interesting parts of making these drawings,” said James.

“I’ve been doing this for about seven years now, mostly part-time, and more recently full-time, and I’ve learnt by trial and error which particular character works.

“If I’m drawing a portrait, and I need to recreate someone’s skin complexion, most people want to be seen in the best light, so even skin tones require a character that has a large surface area, like the ‘@’ symbol.

“That’s also good for shading, which can be achieved by hitting the key more softly.

“If someone has dimples or freckles, then I might use some asterisks, because it’s a much sharper mark, whereas the underscore is a perfect shape for drawing horizontal lines in an architectural drawing, like the bottom of a window sill, or doing brickwork.

“Achieving curves is very difficult, especially if you’re working across multiple sheets, because they all have to line up.

“Typewriters inherently want to go from left to right so they’re great for straight lines, but not so good for verticals and curves.

“So what I’m doing is using my left hand to ever so slightly twist the paragraph lever by a minuscule amount while I’m typing to create a curve, like the roof of The O2, for example.

“I can’t think of any other way of drawing that requires you to use both hands in this way. Your right hand is on the keys and your left hand is responsible for making sure you stamp that mark on a very precise point.

“Once it’s been made that’s it, there’s no way of undoing it – I won’t use Tippex so mistakes become part of the drawing.

From April 1-10, the largest ever exhibition of James’ work ever gathered together is set to be held at Trinity Buoy Wharf, with many of the pieces created at the east London location in Leamouth. Entry is free.

“Visitors will see the biggest collection of my work to date,” said James.

“It’s mostly pieces from London locations, usually drawn on site with views of places like Greenwich Park, the Thames Path and Trinity Buoy Wharf itself.

“What’s also important for the work is to add a second layer of information, so the drawings are not just about piecing together various characters, they also contain concealed messages or hidden lines of text.

“I’ve often done that more recently when I’ve been working on location and I’ve spotted something, or when a thought pops into my head, especially if it’s the middle of winter.

“I did some of the drawings in January and it was pretty cold outside, so a lot of the messages are me complaining how cold it was.”

Every weekday during the exhibition, James will be hosting free workshops for those who’d like to try creating their own typewriter art.

He said: “When people look at my art, usually it’s not enough, they want to know how it’s made.

“The idea is these groups of about five will get to sit in front of a typewriter and have a go.

“It won’t be creating finished masterpieces, but hopefully we’ll have some fun and it will be a start.

“They can bring along pictures to inspire their typing or I can provide them for reference.”

Read more: New team at The Pearson Room deliver fresh flavours