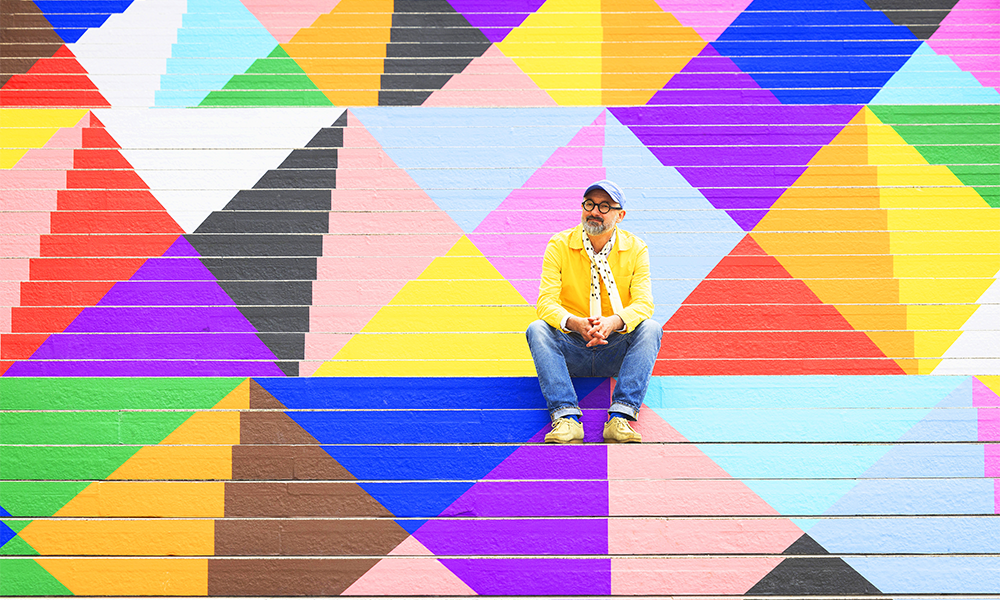

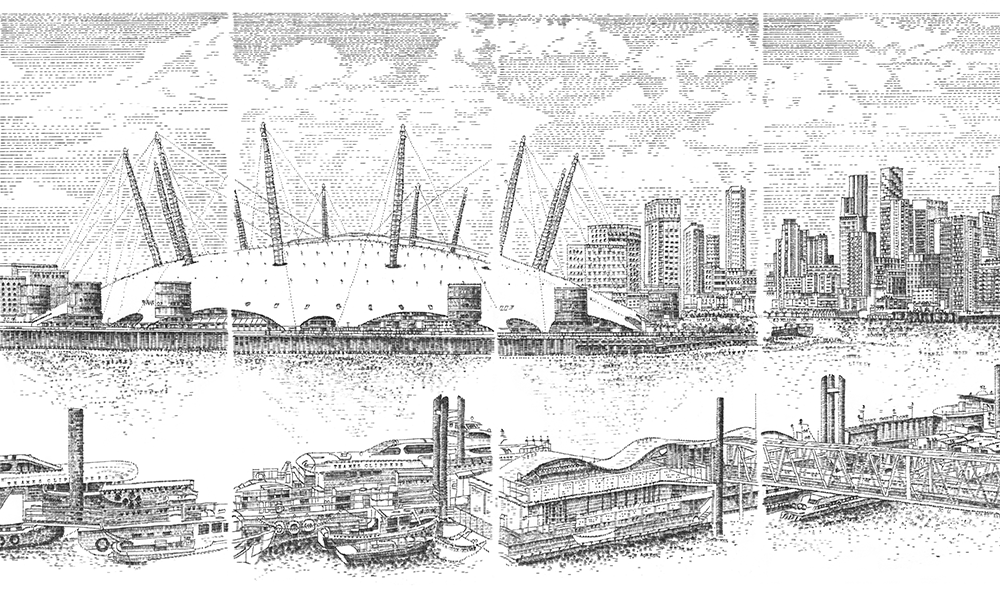

Based at Art Hub Studios in Creekside, Alice has just released a second digital book of her pieces

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s newsletter here

Alice Gur-Arie has always been creative.

“I’ve been writing since I could first hold a pencil and dabbled in various things when I was a teenager in school,” said the artist, currently based at Art Hub Studios in Creekside, Deptford.

A career as an advertising creative and then manager of agencies saw her work first in her native Canada, then North America, Europe and India.

“I’d done what I set out to do – to work internationally in a multi-country environment and I was successful,” she said.

“I wanted to go back to my creative roots – that was 10 years ago – and so I got myself a little studio in Deptford and started to take pictures.

“I also had a lot of photographs from my travels – but I didn’t want to be a straight photographer.”

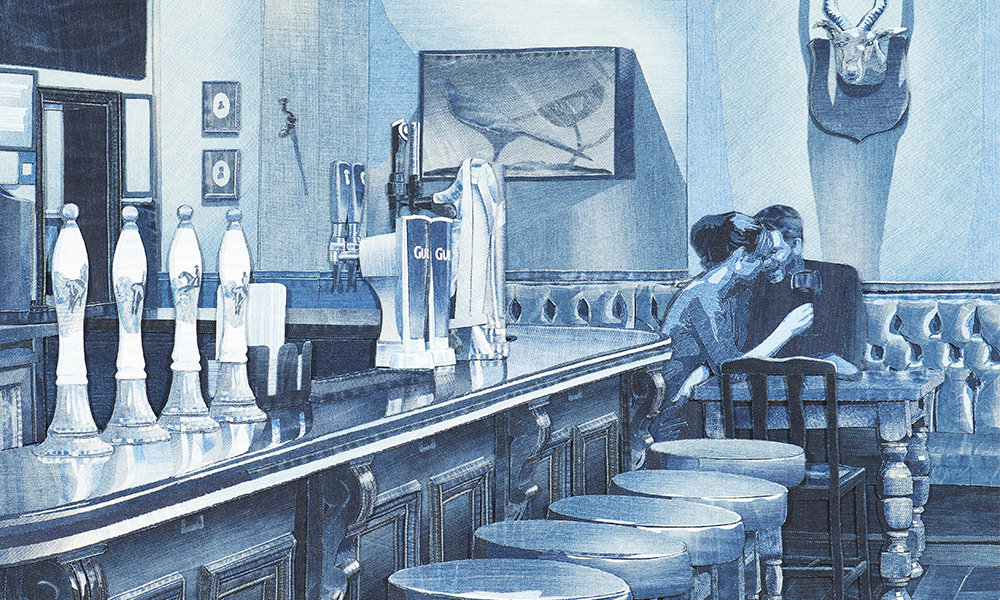

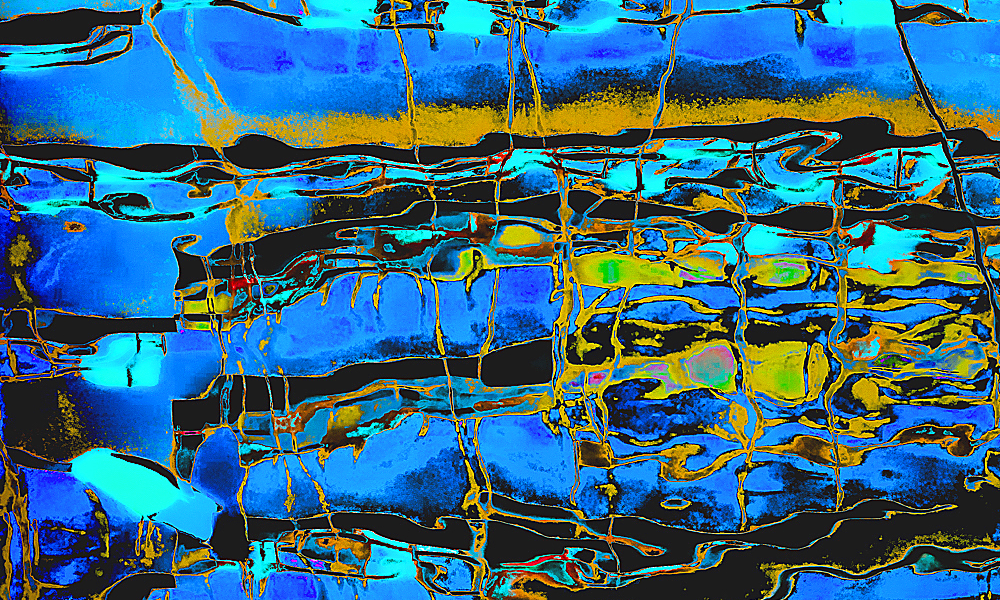

Instead, Alice taught herself to paint her photographs digitally with the aim of creating something new.

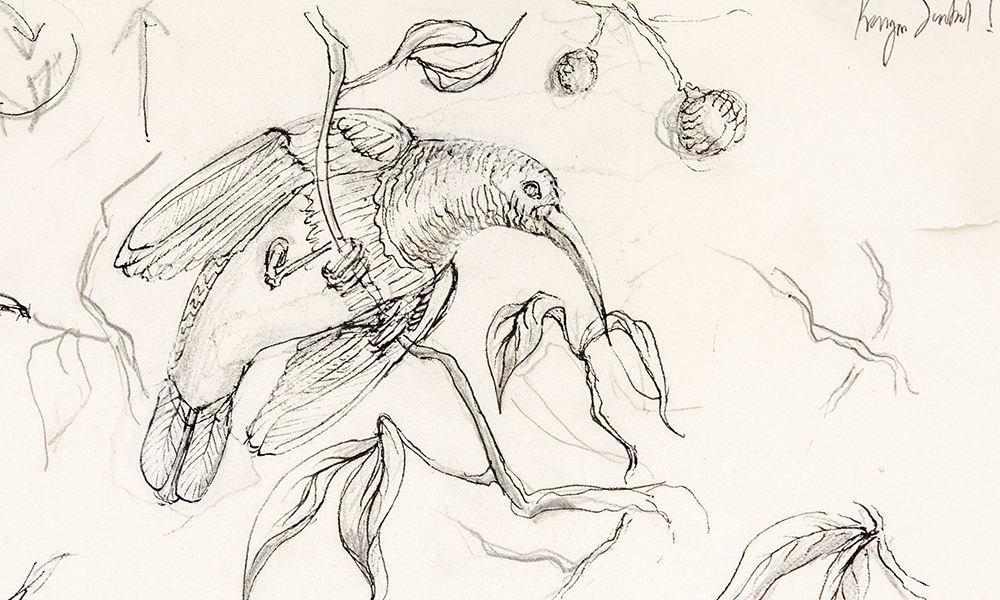

The body of work she has created is varied and extensive, with images that are colourful, monochrome, three dimensional, two dimensional, photographic and almost entirely abstract.

“I never change the composition of the original photograph – it is what it is, it’s like a canvas,” she said.

“When choosing the ones to paint, I have a vision in my head – sometimes I achieve that and sometimes I can’t.

“Sometimes I can do it in several different ways – it’s always possible to repaint images.

“Each time I create an image, it goes back to being a writer, because I’m telling a story. There’s no absolute point where they’re finished.

“I just have to ask whether I’m satisfied with it and whether it says what I want it to say.”

The word, perhaps, for Alice’s creativity is “instinctive”. She looks at a photograph or a collection of objects and imagines what they could become.

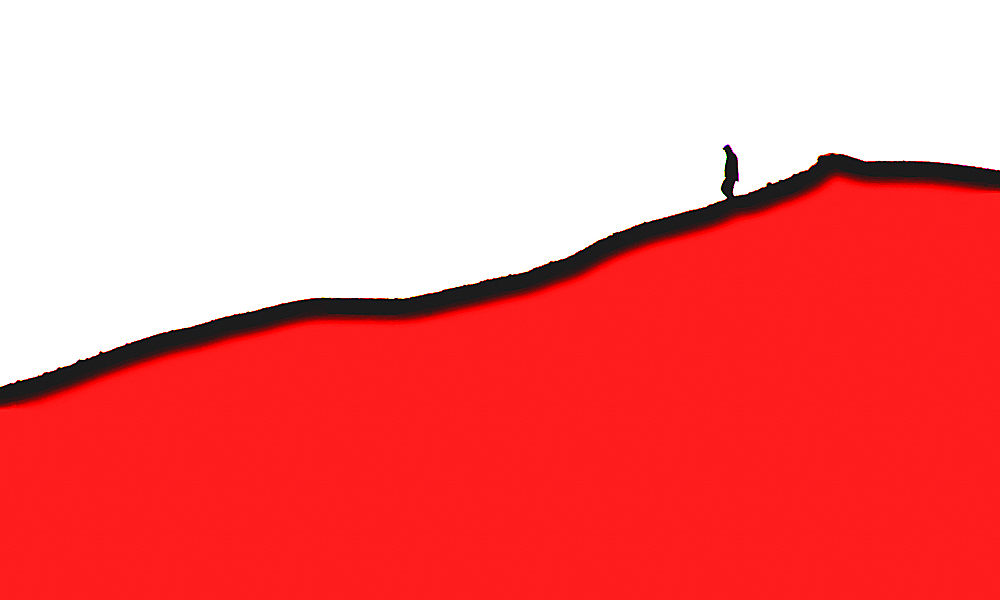

“I have a series called Love On The Rocks,” she said.

“I took the images in Iceland – it was cold and raining while I was taking photos and my husband said he was going for a walk.

“There was a volcanic hill behind us and I took pictures of him as he walked along the ridge. He couldn’t see it, but I could see the outline of a woman in the shape of the hill.

“For another series, I’d always wanted to do something with layered hills.

“In Portugal I got to a summit and just saw this amazing vista in front of me.

“So I started snapping away and, after I’d painted them digitally, I realised there was a romantic story in there, so I called the series The King’s Lodging.

“Each piece within it has its own title and the idea was to tell a story by displaying them together so the viewer could create the narrative in their head.”

Alice’s latest project has been to create a second digital book of her work, based on the Chinese Zodiac.

“I have a friend – John Vollmer – who is an Asian scholar,” she said.

“He sent me a picture of a snake from some archive in celebration of the year of the snake and I thought we could do a better job.

“We started collaborating for the year of the horse – I painted a photograph of the animal and he wrote the text. I wrote a story to go with it and once I’d done that I knew I wanted to do all 12 animals.

“It took a number of years, but the result was my first book Twelve: Shengxiao Zodiac Creatures In Art And Words featuring 32 images and 12 short stories.

“Then John told me about five, which is an important number in Chinese philosophy. That led me to create Five: Wuxing Elements In Art And Words with a foreword by him.”

Alice’s latest digital book features 81 artworks, about 25% of which were made specifically for the project.

“While there are no stories in the book, I have written a poem for each of the elements. I want readers to really respond to the art in Five.

“I love landscapes and seascapes and ‘seeing’ is important to me. I want people to see things in a different way – familiar, but unfamiliar.

“It’s fantastic to have people look at and talk about your work because they see things in it that you don’t.

“For example, I made a piece from a photograph of the tailpiece of a stringed instrument and people saw a boat in the final work.”

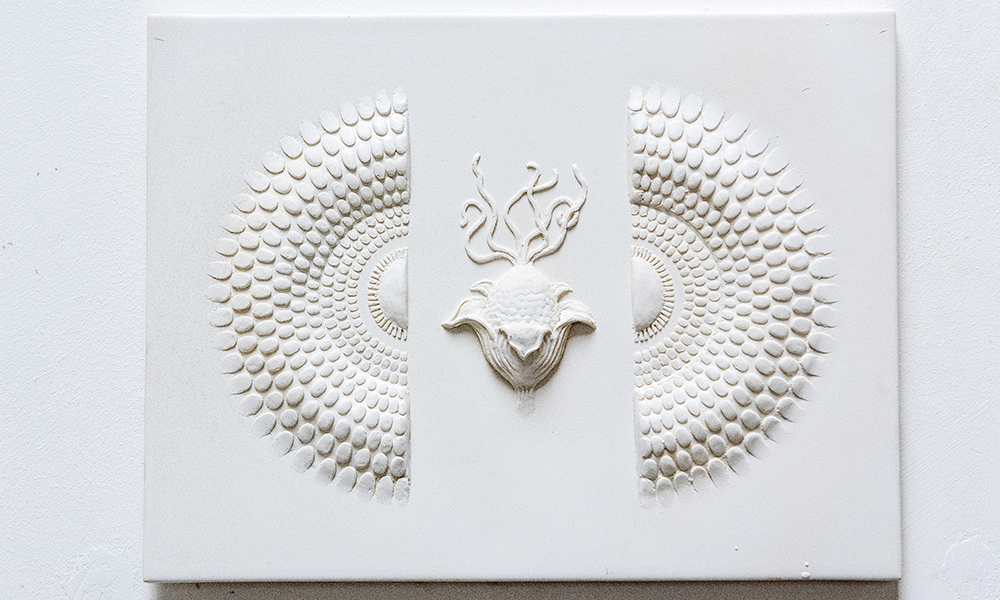

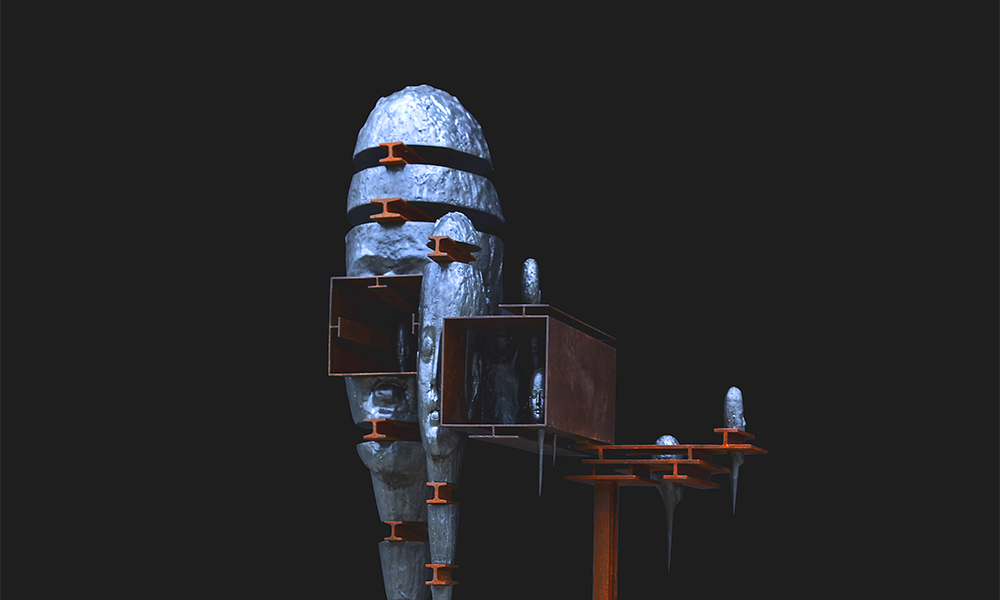

While the majority of Alice’s work is created digitally, she also creates sculptures, including recent pieces using found objects.

“I don’t like sitting at a computer all day long, but my paintings don’t get made if I don’t do some of that,” she said.

“I’ve always loved working with my hands and I have an idea that I will also make collages from my finished digital paintings.

“With the wall hangings, I had some different kinds of rope and just started to play.

“The fairy stones – ones you find that have natural holes – are from the Mediterranean and Ramsgate.

“I’d had them for years, having collected them, and I thought I’d do something with them that has different textures.

“I’m fascinated by texture in all my work. I try to make a big thing of that in my paintings because we live in a world that’s anything but flat.

“First, it’s about the photography. I have to go out and take the image. If I didn’t do that, you wouldn’t have the picture.

“Then the paintings sit within a range – a set of dimensions.

“That means I can achieve results that are more photographic while others are more in the middle or much more abstract.

“I often strive for the sweet spot between those two things that combines them both, but sometimes the painting won’t let me go there.

“They take varying amounts of time – it really depends on the picture and on me.

“I have a painting from India that took me 10 years because I kept going back to it.

“It wasn’t saying to me what I wanted it to say, so I put it away and would bring it out every couple of years and try again until it was finally complete.”

Alice’s works are available for sale online.

Read more: Discover Space Lab at APT Gallery in Deptford

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s newsletter here

- Jon Massey is co-founder and editorial director of Wharf Life and writes about a wide range of subjects in Canary Wharf, Docklands and east London - contact via jon.massey@wharf-life.com