Charity founder and CEO Marcel Baettig on the importance of providing space for artists

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

BY LAURA ENFIELD

When the mini budget was announced last week, charities were left mostly empty-handed. It is a scenario Marcel Baettig, founder and CEO of Bow Arts, is well used to.

For the last 27 years, he has worked to generate the means to provide affordable workspaces and steady incomes for artists in Tower Hamlets.

Along the way, the charity has missed out on grants to help buy property, survive Covid and pay energy bills.

But it has thrived through a model that allows it to offer subsidised rents to artists and employment in creative projects for schools and community groups.

It has grown from supporting 50 artists to 500 and from one site – its headquarters in Bow Road – to operating in 15 locations spread across London.

Until now, it has only rented space.

But after more than two decades it has finally entered a new era with the purchase of its first building – on the ground floor of the Three Waters development at the meeting of the River Lea and Limehouse Cut canal.

“I’m absolutely thrilled,” said Marcel, a trained sculptor who established the charity in 1994.

“This secures our future. The aim has always been to use the income we generate from our buildings to support creative community services, like work in schools, public art galleries and different sorts of events.

“We have been very unlucky with our timing.

“When we grew and property was affordable, there were grants around for organisations like ours to help buy buildings.

“But we were just a bit late and all the money had been given out.

“So we’ve had to be very steadfast, slowly save our pennies and get ourselves into a position where we could afford to buy something.

“We’ve eventually managed to do that through the partnerships that we set up about five or six years ago with housing association Peabody.”

Nine months ago, it approached Bow Arts to create a permanent creative space on the ground floor of the scheme – a joint project with developer Mount Anvil – as part of its community contributions.

“We had been trying to buy something for a long time,” said Marcel.

“It’s the only way we can maintain low rents for artists and guarantee support for them in the future. If we have a landlord, they can put the rent up and then, so would we.”

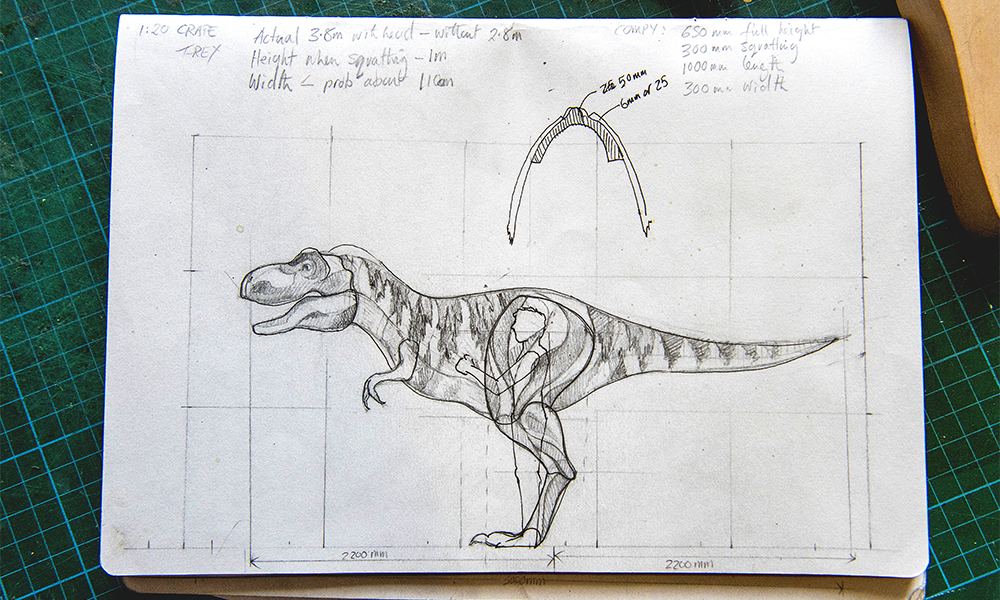

The 57-year-old was inspired to set up Bow Arts after his own struggles as a sculptor.

He said: “I had quite a successful career but the trouble with this type of work is that it’s project-based and when you get to the end of that bubble, you have to start all over again.

“It might be six months before you get another commission if you’re lucky.

“So that was quite a hard way to live.

“I just had the idea that if I could get a collective space, where there would be a group of people doing the same sorts of things, then we could control the rent by sharing it and share all the resources.

“I also happened to do quite a lot of education work in schools and with special needs groups – I knew artists had a lot of transferable skills.

“I thought it would be a way to get work and build up relationships in an area.”

He found an ally in Marc Schimmel, who had just supported Damien Hirst and helped kick off the Brit Art movement.

“He offered me Bow Road and helped me set up the charity – we were full within three months,” said Marcel.

“I’m the only failure, as I’m the one that hasn’t been able to go back to being an artist.”

The charity began saving for a deposit, but found it couldn’t keep pace with property prices no matter how fast it saved.

“We had finally saved £1million and my big fear was that we were going to lose all of that through the pandemic,” said Marcel.

“Luckily, we were able to hang on to it, which meant we just about had enough to get a mortgage and buy this property for £2.2million.

“Where we get hit as a charity it is because none of our artists are higher earners – they are all below the VAT threshold so we’re not registered for VAT and we don’t charge VAT.

“But we have to pay it on the purchase – another £500,000 – and then the extra 20% for the fit-out. It is hard to make it affordable for artists.

“You’re constantly trying to work with the government or HMRC to find ways around it, but there is no provision to support the third sector in doing what it could do very well in this country.

“It’s a real shame considering charities have taken on an awful lot of local services for councils over the past 10 years.

“A tax break would make a huge difference to us and so many other organisations.”

All of Bow Arts’ education work stopped during lockdown, but it was able to get some financial support from places like the Arts Council and the GLA to help artists keep renting their studios.

Even so, it lost about 20% of its tenants and Marcel said the energy crisis had hit just as things were starting to bounce back.

“None of the mainstream stuff ever comes to us because we’re a charity and it’s all targeted at businesses,” he said.

“We will try the best we can to get grants, but as artists, we’re used to not having a lot of money so we’ll just be putting on thick jumpers.”

Marcel said the charity had finally managed to achieve its goal of a permanent site now the property market was changing.

“People are asking themselves if they are going to get these prices for commercial space and what the alternatives are,” he said.

“Then there’s been a lot of interest in the creative sector and in this new area of business.

“Over the last five years, there has been a real sea-change in London and awareness of the strength and the power of the creative economy.

“There are a lot of empty buildings around and people have looked to organisations like ours who have many years experience in filling these buildings and keeping them full.”

Bow Arts’ low rents – which range from £100-£500 per month- have seen it stay 98% full since day one.

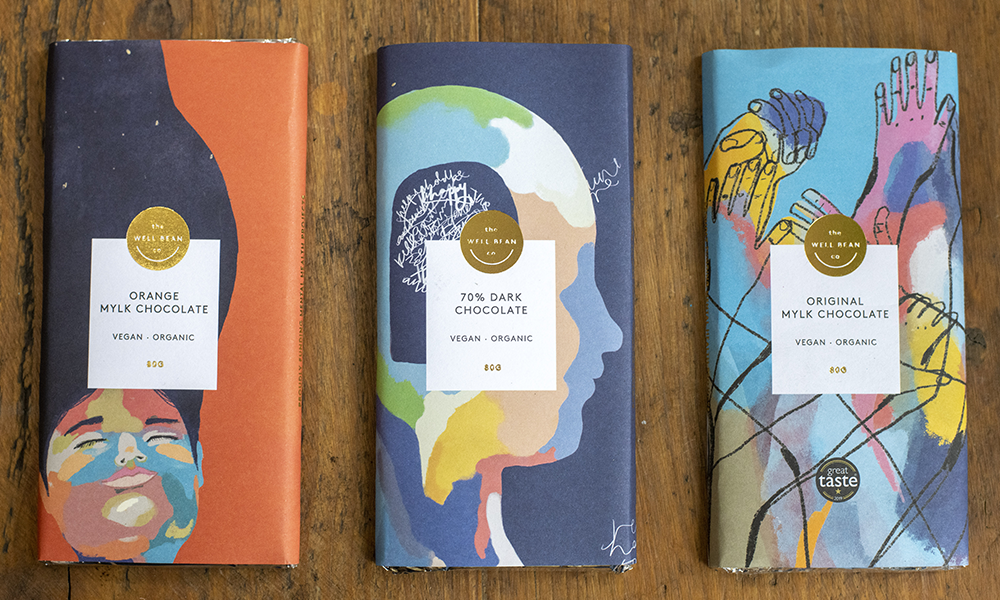

The charity creates a circular economy by ploughing at least 25% of that money into supplying services for the surrounding local area, such as arts programmes for schools and community groups.

It trains its artists to be the ones who deliver that work and they get paid for doing it.

The charity is overwhelmed by the demand for what it does, getting about 12,000 hits a month from artists looking for space.

Marcel said it began building relationships with developers a few years ago to try to increase its supply of studios.

“We have worked with the GLA for many years because there is a creative workspace crisis in London with over 50% expected to be lost in the next few years,” he said.

“We started to form proper partnerships with organisations like Peabody, Notting Hill Genesis and Mount Anvil because they’re the guys that are building new places and we can work together to deliver creative workspaces.

“What has been quite incredible is the value added by building an artist community that works with local schools and organisations.

“That has meant a lot of commercial landlords and local authorities have actually given us buildings at very reduced rates, so that we can actually develop this creative placemaking.”

Bow Arts first began working with Peabody in 2015 as a partner on its huge Thamesmead regeneration project.

The old Lakeside Centre was transformed into 40 artists’ studios, a community nursery, kitchens and a cafe.

Its plans for the 26,000sq ft of space at Three Waters will see it converted into 70 studios.

Set to open in January, the launch will be celebrated with the award of the East London Art Prize, run by Bow Arts in conjunction with the V&A, UCL and the Whitechapel Gallery.

“It has grown out of the East London Painting Prize and is all about encouraging new artists and promoting them, to bring as many into view as possible,” said Marcel.

“We’ve had 670 applicants, which is phenomenal, and shows how many artists are out there.”

The shortlist will be announced at the opening of Three Waters with an exhibition of work held at the charity’s Nunnery Gallery in Bow.

The winner will get a cash prize, free workspace, an exhibition and support for two years until the prize is awarded again.

“It is really hard for young artists in those early stages,” said Marcel.

“So an organisation like Bow Arts, which is absolutely committed to supporting them and maintaining affordable rent levels, is vital.

“There’s so much talent out there and, as London pushes east, we’re opening up more markets for people who want to go into the creative sector.

“It’s become a very viable career.”

Bow Arts also supports the next generation of artists through its work with 100 schools across London.

“We train artists very carefully to be able to deliver workshops, activities, commissions and things like that,” said Marcel.

“Then we’ll develop long-term roles and partnerships with the individual schools and with consortium groups of schools to deliver a creative programme.

“A lot of the creativity has been taken out of the curriculum in mainstream schools.

“We want to expand that operation and Three Waters means there will be permanent funding to support that work in Tower Hamlets and Newham, which will have a huge impact.

“There’s so much talent in the area.

“So many people from less privileged backgrounds just simply don’t know how to access the arts or even understand that there is a potential career for them there.

“We’re giving them those opportunities.”

Looking back, Marcel said it was strange how he’d changed alongside the charity, finding a new career without even realising.

“I would never have expected this if I’m very honest, as I always saw myself as an artist,” he said.

“I couldn’t have stayed as enthusiastic about it if it wasn’t such interesting work with interesting people.

“I don’t just mean the creative community, it’s everyone we get to work with – developers, schools and the local community.

“The support we’ve had and the interest from people has been really quite amazing.

“So I have been distracted by this for the past 27 years and that time has really flown by.”

Read more: Discover east London firefighter Stephen Dudeney’s book

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to Wharf Life’s weekly newsletter here

- Laura Enfield is a regular contributor to Wharf Life, writing about a wide range of subjects across Docklands and east London