Immersive experience welcomes visitors into a mysterious world of canals and platypuses

Subscribe to our Wharf Whispers newsletter here

…we’re on the trail of a missing package, but something sinister is going on. There’s blackmail, a robotic AI doctor that’s scathing about our putrid human bodies, a curious undertaker, odd business cards, a disgusted scientist and TVs that play sinister messages when tuned to the right channel. Oh, and there’s something just not quite right about that mayor…

Welcome to the strange, uncanny world of Phantom Peak.

The comic book adjectives seem appropriate for an immersive experience that aims to place those attending right in the middle of a larger than life narrative.

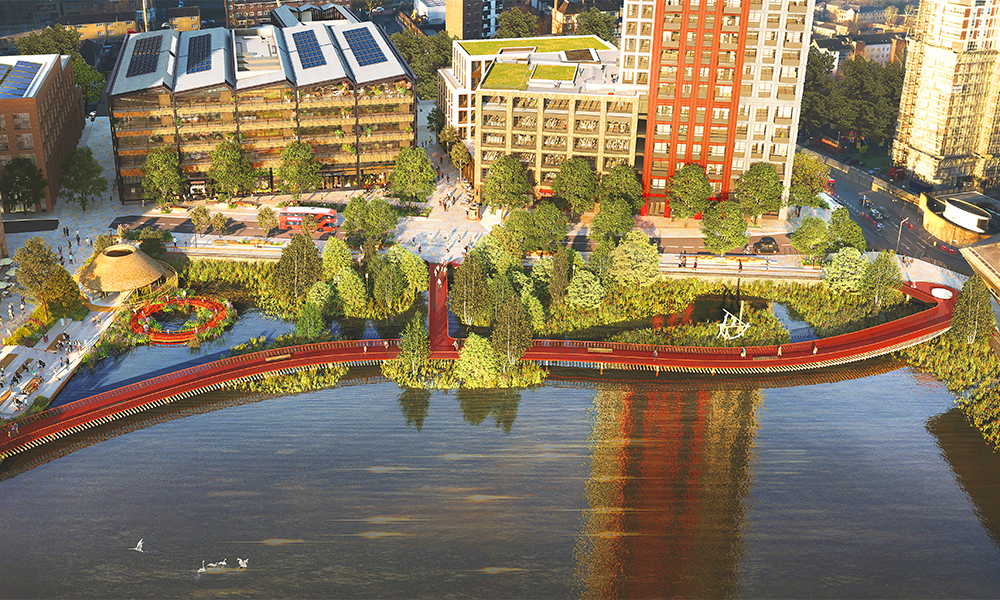

Located a short walk from Canada Water station inside and outside a disused industrial building, the venue promises a fully realised steampunk town complete with canals, waterfalls and residents to interact with.

But things don’t stand still.

The place may have opened a little over a year ago, but it’s just launched its fifth season – the latest chapter in a complex, involved saga designed to keep people coming back for more.

Each time it resets, there are fresh characters to meet, new mysteries to solve and adventures to go on – an approach that for co-founder Nick Moran is akin to another medium altogether.

“When you come to Phantom Peak, you’re essentially coming to a real-life, open world, role-playing video game,” he said.

“It’s up to you whether you walk to the hills and carry on walking or spend your time crafting minerals – you can do what you like.

“It’s all about player agency, creating a world where people can explore and experience many different things.

“You can do all the events that the townsfolk run all day, or you can follow the trails and the stories.

“It’s not like immersive theatre where you don’t know what you’re doing – you’re guided through the experiences.”

The setting is Phantom Peak, a cultish sort of town in the grip of corporate entity Jonaco, which rebuilt the place after a suspicious blimp accident, founded and controlled by the buff, messianic figure of Jonas.

Visitors are encouraged to download an app and answer questions to find a quest to follow – although everyone is equally free just to wander around chatting to the townsfolk, playing games and indulging in the street food and beverages on offer from the various outlets.

It’s extensive, expansive and – because of the myriad paths on offer – filled with eager puzzle-solvers hunting solutions, intrigue and adventure.

Oh, and there’s a platypus hooking game in honour of the town’s peculiar mascot.

“This place was an abandoned warehouse and a car park when we came here,” said Nick.

“We’ve transformed it and it’s impossible to do everything at Phantom Peak on a single visit.

“Each time – whether you come with your friends or your family – it will be different, with new stories and trails to explore.

“Then, each season, we create a new chapter in the life of the town – some characters may have gone, others will remain, but there will always be something new and it allows us to move forward or backwards in time with the narrative. “

That’s an aspect Nick and the team take extremely seriously.

Following a degree in classics he trained in writing for the stage and screen before working to create live experiences around newly published books.

This led to a job as creative director of Time Run – a pair of escape room-style games that welcomed thousands of competitors through their doors.

He then performed the same role for The Game Is Now, an immersive experience – officially tied into TV series Sherlock – which he co-wrote with Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat.

The puzzle, which features Gatiss, Benedict Cumberbatch, Martin Freeman and Andrew Scott, continues to run in west London.

But, having teamed up with set-building expert Glen Hughes, Nick wanted to create something that went beyond the medium of escaping from a room.

“We decided we wanted to do something that would combine all the things we liked about immersive experiences – gamification, storytelling, open world, choice and being able to sit and relax too,” said Nick.

“Escape rooms are all about high engagement, high throughput and pushing people from one thing to the next.

“Phantom Peak isn’t like that. It’s about being as engaged as you want to be. It’s all about stories – less a fundamentally passive theatre experience than a place where you can take on a role.

“We wanted it to be a world of play – man-made canals, platypuses, a huge muscular impresario named Jonas.

“From there the stories write themselves – but we take it seriously. It’s like making a TV show.

“There’s a writers’ room where we think about the characters and how we can make the narratives resonate with people.

“It’s novelistic – a place that has real depth, where there’s lots to explore but also lots to do.

“It’s like the platypus itself, the mascot of the town. It’s neither one thing nor another – not quite a mammal, not quite a bird.

“But it’s the symbol of the place and the townsfolk love it.

“Some of the actors we have working here have been with us since we opened and they’ve really grown with the town.

“They are as much a part of the place as anything in the stories and it’s been a real pleasure to see it develop that way.”

Nick and Glen are currently raising funds to expand Phantom Peak globally.

- Tickets for Phantom Peak start at £19, with experiences lasting up to four and a half hours. Use code WHARF20 for 20% off. Shows take place on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Read more: How Wharf Wellness is set to fill Canary Wharf with calm

Read Wharf Life’s e-edition here

Subscribe to our Wharf Whispers newsletter here

- Jon Massey is co-founder and editorial director of Wharf Life and writes about a wide range of subjects in Canary Wharf, Docklands and east London - contact via jon.massey@wharf-life.com